By Audra Krake, M.S., and Robyn Brinkerhoff, Ph.D., Special AFS Contributors

New workouts and fitness facilities, while offering exciting opportunities to attract and engage fitness clientele, also present opportunities for accidents and injuries.

For any fitness studio, consideration of the possible risks associated with the facility, equipment, and/or activity, and how to minimize those risks, can help increase safety, reduce the likelihood of an injury, and more effectively combat litigation.

Some commonplace strategies (e.g., liability waivers, warnings signage, documented emergency-response plans; see AFS Studio Success E-book, chapter 13 by Stephen J. Tharrett, M.S., for further information) may already be well-known to studio operators. However, as a professional involved in investigating fitness-related accidents within the context of litigation, I have a unique perspective on what other types of available information might contribute to an effective risk assessment.

In this article, I describe some of these sources that you may be unfamiliar with so that you might consider using them in your risk assessment for your facility.

Manufacturer’s Documentation

Manufacturer-supplied materials (e.g., product warning labels, User/Owner’s Manuals, Assembly/Maintenance instructions) can provide a wealth of valuable safety-related information regarding important precautions to take during setup, operation, and maintenance of equipment. Safety-related information can be conveyed not only within explicit “Warnings” or “Safety” sections of such documents but also within instructional sections. For convenience, such information can often be accessed, downloaded, and/or searched, on manufacturer websites.

Industry Standards

For some equipment, there are associated industry standards from organizations such as the American Society for Testing and Materials, which may contain safety-related guidelines such as suggested warning labels. These standards typically can be found and purchased online for immediate download.

Comparable Products/Activities

Consider the safety measures employed for other comparable activities or products. For example, if introducing rowing machines into your studio for the first time, look into the safety precautions for other brands of rowing machines (e.g., via documentation on manufacturers’ websites) in addition to those of the particular brand you are using, and investigate the practices of other studios operating a similar piece of equipment.

Injury data

Some of the best evidence for risk assessment comes from actual injury data. Numerous scientific research articles on real-world injuries associated with different fitness activities can be found online through research article portals such as Google Scholar (https://scholar.google.com/), by using search terms relevant to the activity or equipment of interest (e.g., “rowing machine injuries”).

You can also search the website of the United States Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC), (https://www.cpsc.gov/), which provides numerous articles and safety advisories on all kinds of consumer products. The CPSC also provides direct public access to a searchable online database of injuries observed in emergency departments across the United States, the National Electronic Injury Surveillance System (NEISS) (https://cpsc.gov/Research–Statistics/NEISS-Injury-Data).

The database provides brief narratives about the activity performed and the resulting injury, and is searchable by the product/activity associated with the injury (e.g., exercise equipment, weight lifting, trampolines), among other things. For example, the narrative “52 YR OLD MALE FELL OFF STATIONARY BIKE ONTO THIGH WITH HEMATOMA” is coded for the product of “Exercise equipment,” along with the injured party’s age (52), gender (male), diagnosis (hematoma), injured body part (upper leg), and locale where the injury occurred (place of recreation or sports). A sample analysis of data from this database is described in the following section.

Example Analysis of Data from the Consumer Products Safety Commission’s NEISS Database

Let’s say I wanted to investigate the most common injury scenarios associated with indoor cycling or spinning, using the CPSC’s injury database mentioned above. I could use their online system to query the database for injuries associated with exercise equipment that occurred within the year 2016.

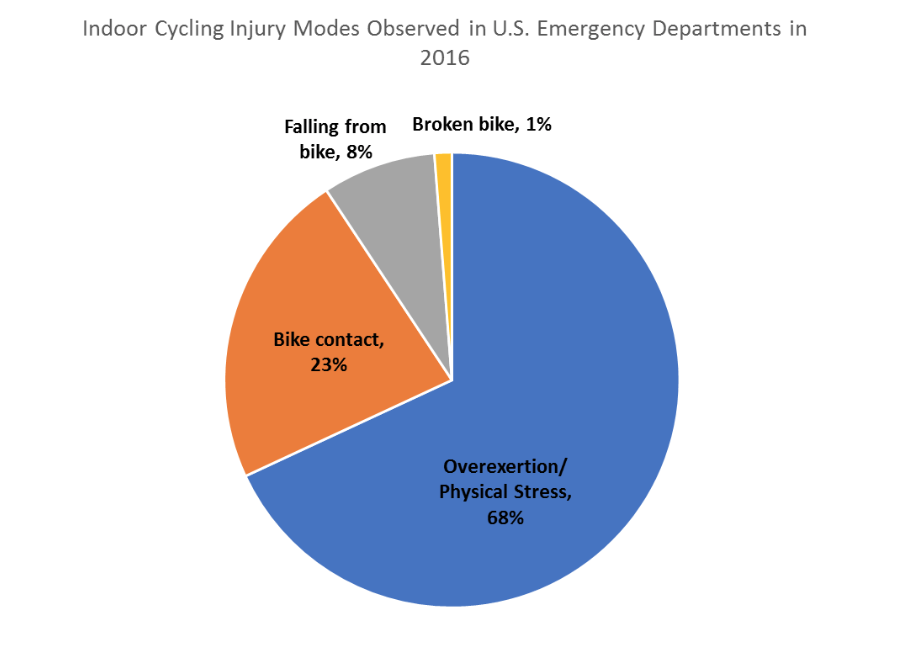

Note that, per CPSC’s coding methods, this product category does not include on-road and mountain bicycles. After filtering the results to include only patients 18 and over, analysis of the bike-specific incidents (identified by using the search terms “bicycle,” “bike,” “cycle,” and “spin”) provides insight into the most common reasons for spinning-related injuries. By far the most frequent mode of injury at 68% is physical stress or overexertion (e.g., soreness, back pain, rhabdomyolysis, sprain/strain, dizziness, syncope (fainting)).

The second most frequent mode of injury, “Bike contact,” (23%) involves inadvertent contact with the bike while riding or while performing activity near or around the bike (e.g., tripping over a bike, falling onto a bike, getting hit in the shin by a pedal). 8% of injuries occurred due to falling off the bike, most typically when mounting or dismounting the bike (e.g., fell when getting off bike). Finally, a relatively small percentage of incidents involved a bike part breaking (e.g., handlebar) (1%).

Conclusions

So what does data like this tell us? In this case, the real-world injury data indicate that the greatest risks from indoor cycling are the same as you would expect from any other physical activity (overexertion) or a large object with moving parts (tripping over/falling onto the bike or getting hit by a pedal). Review of industry standards and warning labels on indoor cycles on the market reveals that consistent with these findings, the common practice is to warn users to always consult with a medical professional before starting an exercise program, to stop the workout and consult a physician immediately upon feeling pain or abnormal symptoms, and to keep body, hair and clothing away from all moving parts.

In summary, there are a number of different ways you can assess risk for the activities performed in your studio. Of course, you can never eliminate all accidents and injuries. However, complying with available information and guidelines can serve to demonstrate that your facility is acting upon the best available data, and/or following common and accepted practices within your industry.

Robyn Brinkerhoff, Ph.D. is a human factors scientist at Exponent, a science and engineering consulting firm. She earned her Ph.D. in Cognitive Psychology from UCLA and applies her knowledge of human behavior, capabilities, and limitations to the study of how people perform in everyday situations and environments, such as while using fitness equipment or navigating public spaces. Dr. Brinkerhoff frequently acts as a consultant to investigate accidents, provide expert opinions for litigation, and advise on the development of product labels and instruction manuals.

Audra Krake, M.S. is a human factors scientist at Exponent. She earned her M.S. in Kinesiology from California State University, Long Beach, with a specialty in Exercise Science, and analyzes human factors and human performance in the context of use of consumer products, such as while using sports and exercise equipment. Ms. Krake utilizes her expertise in human movement and information-processing to evaluate issues related to motor control, decision-making, and the effects of inattention and distraction as they relate to accidents, injuries, product usage, fitness training, and technique.